Lead bullets for artists in Buenos Aires

The General San Martín Cutural Centre, (CCGSM) which depends on the government of the City of Buenos Aires, is the largest public cultural center of Argentina and one of the most prestigious in Latin America. Its audiences had reached around 300,000 spectators annually, and even hosted for some time the CONADEP (National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons) and the city’s legislature body. However, since January this year, the building has been militarized by the city government, with numerous metropolitan police officers and unidentified security personnel circulating its facilities and with all the activities suspended. This is how those in charge of “culture” in the city of Buenos Aires chose to solve a long-standing conflict, featuring artists and students who resist the closure of a space housed within the CCGSM: The historical Alberdi Hall.

At nigth on Wednesday, an operation by the Metropolitan Police seriously escalated the level of violence of the conflict trying to evict forcefully the protesters who were carrying out a cultural camp at the square adjacent to the complex, causing at least three gunshot wounds: I was hit by a lead bullet that perforated my thigh, by a Metropolitan police officer who shot me at the intersection of Corrientes Avenue and Paraná Street,

said a journalist of the Alternative Media Network, then transferred to the Durand Hospital, whose name, along with that of a photographer of the same organization, are on the list of at least three people wounded by bullets that were registered on that day.

The Alberdi Hall

The Juan Bautista Alberdi Hall was created by the Art Education Department of the city over 25 years ago. It can accommodate about 200 spectators and works independently from CCGSM, although it is located on the sixth floor of the huge complex located at Sarmiento and Paraná. With a history of high-quality shows, it offered drama workshops for children, acting introduction courses for youth, acting courses for advanced students, musical comedy for youth and adolescents, as well as photography, puppetry, visual and artistic production, among others, all of them for free and with a popular orientation.

In September 2009, Judge Fabiana Schafrik ordered the city government to refrain from closing the Alberdi Hall, confirming an injunction driven by a group of summoned teachers and students resisting the undercover dismantling of the space (within the context of rumors about the privatization of the whole complex). The judge said that the city government should commit to safeguarding the activities that take place in the hall, given their importance for the community,

according to comments in 2010 by Gabriela Villalonga, the hall’s teacher that appears as the holder of the writ for amparo (constitutional protection). Since then a long legal battle began, along with the progressive deactivation of the entire complex within the context of a supposed “renewal” project to be carried out by the Macri administration — an undercover privatization process — that remained unfinished in the end. Practically, the Alberdi Hall maintained a continuous operative schedule since then. The city government sought and still seeks to transfer the hall’s activities to a space located in the neighborhood of Chacarita that doesn’t even have a stage, which was already insufficient for the activities carried out on site, and whose building conditions are not better than those of the Cultural Centre (the excuse for the government requesting the transfer was the bad building conditions of the CCGSM).

In 2010, and as part of a plan of struggle and selfmanagement, a peaceful occupation of the hall began, keeping many of the workshops, free or financed by passing the cap*, as well as lectures, discussions, festivals and even a copyleft film series. As Martín Salazar, actor, director and member of *Los Macocos theatre group wrote at Página/12 newspaper:

A couple of years ago I had to run an errand in the building and walked up the stairs: besides the fact that they rarely work, the lifts are not serviceable appliances whose maintenance inspire much trust. That’s how I got a close view of the state of carelessness in which the Cultural Centre was. I felt great sadness to see such large, generous spaces, waiting for someone to manage them accordingly. In such an important city, the CCGSM should be a receiving antenna for new trends, a place to evaluate the works that don’t fit in more orthodox theaters or halls. Everything was infused with apathy and neglect, but on the sixth floor was a group of people attending a philosophy lecture, and there were people in the theater room preparing the show for that night. That floor was all color, it had facilities, people working and very open to receive proposals to offer in that beautiful theater, which had an extensive and varied schedule of shows, with a selection of proposals according to ‘blockbuster’ days.

The people who infused life into that space were gunned the other day.”

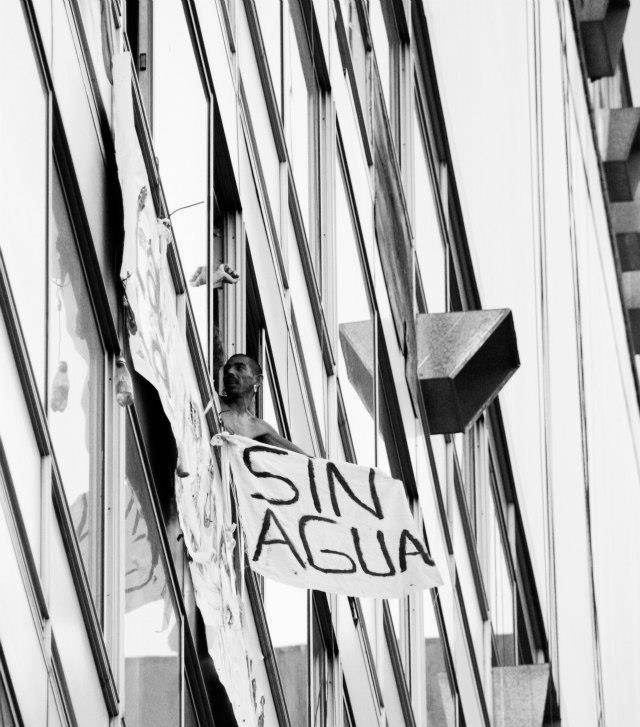

In late 2012, with the recess of summer activities, the Government sought to evict the entire cultural complex and thus terminate with the occupation of the sixth floor, worsening the conflict. Since that day a small group of students remains occupying the room on the sixth floor, without food or access to the bathrooms, and a camping in the square adjacent to the building provides them with the essentials (using a rope). The camp keeps conducting cultural activities, maintaining at all costs the agenda of the Alberdi Hall. Artists like Vox Dei, Javier Calamaro and Arbolito participated in the events, and numerous prominent theater figures gave their support, including Dario Grandinetti, Diego Capusotto, Natalia Oreiro, Rodrigo de la Serna and María Valenzuela, who showed their support in this video, saying I am also the Alberdi Hall

.

Lack of information

When the conflict attracted the attention of the media, the coverage was particularly partial and tendentious, if not manifestly unfortunate. If it were a conventional public school, and students and teachers with white dust covers were struggling against a measure of privatization or covert emptying —with an injunction in their hands— it’s likely that the weight of the media stigmatization wouldn’t have fallen on those responsible for carrying out the protest — quite the opposite. But in the case of the artists of the Alberdi Hall —suitably qualified as “squatters” by various media, and by the city’s minister of culture himself— the burden of proof seems to have been reversed and the workshop organizers must demonstrate at all times the legitimacy —or at least the relevance— of their complaints, despite having favorable court rulings, a renowned and popular trajectory of free and popular activities, and support of theater workers and their union.

Actually, what should cause a scandal are the excesses perpetrated by state power, keeping a small group of students isolated, deprived of access to toilets or food for several weeks —as if they were taking hostages, instead of exercising their right of protesting through a peaceful occupation—, in the context of a policy of intimidation and threats, and placing the protection of material goods above the physical integrity of people: “I was followed all the way home, one of our colleagues was beaten by some guys wearing civil attire, another person was arrested in the surroundings of the hall and was kidnapped, locked in a car for three hours, a fellow juggler was confronted by people that came out of a car, they beat him and told him ‘stop fucking around with what you’re doing, next time we’ll directly disappear you’,” said one participant of the camping a few days ago.

Criminalization

According to the head of the Office of the Ombudsman of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, Alicia Pierini, the responsibility for the possible consequences of an escalation of the conflict are quite clear:

[…] City officials involved in cultural management have failed to manage the conflict constructively and instead, resorted to the penal system. It is necessary to clarify that the criminal prosecution of a protest is an expression of violence, politically more serious than the “usurpation,” which is also an action of fact and not of law.

To ask the judges to exercise coercion seems to be of law… until the police arrives and “follows orders” in its own way. We have seen it: in the taking of hostages, the police know how to open a dialogue, but in the taking of spaces —by either squatters or street vendors— they don’t.

Culture officials have chosen to criminalize this protest, tenaciously carried out by a paltry group. So instead of opening a channel to de-escalate the conflict, they increased and radicalized it. This is the concern that we have as a body of rights and guarantees: we sense an escalation coming, with risks of rights violations.

So far the only conflict resolution proposal that the government of Mauricio Macri has outlined is pure and simple state violence —despite being an area by definition refractory to brutality, intimidation and ignorance— focusing these days on the “damage to art works” allegedly perpetrated by the workshop organizers, to trigger and justify even harsher crackdowns.

Minister Lombardi besides the Kwakiutl Totem, “cut” and then sawed into pieces “for restoration”.

Minister Lombardi besides the Kwakiutl Totem, “cut” and then sawed into pieces “for restoration”.

But if you really want to get acquainted with the interest shown by the present government in preserving the cultural heritage of the city, just remember the picture of the Minister of Culture Hernán Lombardi posing next to the downed Kwakiutl monument donated by the Canadian government, which the minister ordered to be cut into pieces with a chainsaw and then sent to an open-air municipal terrain to perform restoration work on it

… but an unfortunate graffiti painted on a Le Parc piece at CCGSM will suffice to jail more than one art student or worker who have risked themselves for defending popular art.

A single sentence would be sufficient for the occupants of the Alberdi Hall to summarize the whole thing: «yo estoy al derecho, dado vuelta estás vos…»*

Footnotes

(*) Literally: “I’m on the right, you’re turned”, which means “I’m on the right, you’re meesed up” (from the lyrics of “El Cieguito Volador” by Sumo

Update:

During the night of March 25th, the four artists that kept the occupation on the 6th floor of the Centro Cultural San Martín left the place — according to what the assembly had decided. As the members of the collective said at the press conference, the assembly prefered to preserve occupant’s physical integrity considering the inflexible action of the government: In the presence of this intransigence and the 80 days our comrades spent shut in, we prefer to preserve their integrity and that the comrades come down by will to avoid being criminalize, because if there was someone to criminalize, it had to be the thousand people who are carrying out this struggle […] We fear for their integrity in a fully militarized building, where they had received more than a threat and whipping from unidentified people, as well as from the same metropolitana police

. Representatives of the collective protest, together with their lawyer, the ex congressman Luis Zamora, negotiated the way out of the four artists with the authorities. The artist were not detainee even though it was impossible to avoid their identification by judicial authorities.

On the other hand, a lawsuit against policemen and civil servants was filed due to the repression of March 12th in the surrounding area of the Centro Cultural San Martín, which final balance were more than a hundred injured by rubber bullets, three injured by lead bullets and a youg woman with a fractured skull. In relation to these facts, the CORREPI (Coordinator Againsts Police and Institutional Repression) lawyer María del Carmen Verdú noted that there was not a crazy person who decided to use a weapon but a political order. The State is the one that organizes and runs the repressive force: a policeman does not decide himself what to do in such an event

. Likewise, she emphasized the fact that the ones who received the lead bullets are independent media workers: What we want to prove in the criminal case is that the order was that there shall not be graphic or filmed records about what was happening

. It is not accidental that during the recent repression facts against workers of the Hospital Borda —carried out by the metropolitana police— many journalists, cameramen and media assistants who were covering the news were severe injured.

The Open Assembly of the Sala Alberdi continues to organize and join protest actions and cultural festivals all over the city:

Far from dying is the seed born from this struggle. Now it comes up to multiply and become strong and it will occupy ten spaces and then one hundred a then a thousand. Always temporarily, until the machinery discoveres and supresses it. Always one step ahead, reinventing itself and growing in each encounter.

A 12-minute documentary, which summarizes the history of the conflict:

Also:

- Read this excellent chronicle: “Sala Alberdi: Represión, batallas culturales y ladrones de bicicletas”.

- Take a look at these pictures: “Sala Alberdi: Acampe, espera, desalojo y represión”.