Kettling WikiLeaks

Kettling Wikileaks

by Richard Stallman

The Anonymous web protests are the Internet equivalent of a mass demonstration. It’s a mistake to call them hacking (playful cleverness) or cracking (security breaking). The LOIC program that protesters use is prepackaged, so no cleverness is needed to run it, and it does not break any computer’s security. The protesters have not tried to take control of Amazon’s web site, or extract any data from MasterCard. They enter through the site’s front door, and it can’t cope with so many visitors.

Calling these protests “DDOS attacks” is misleading too. A DDOS attack properly speaking is done with thousands of “zombie” computers. Someone broke the security of those computers (often with a virus) and took remote control of them, then rigged them up as a “botnet” to do in unison whatever he directs (in this case, to overload a server). By contrast, the Anonymous protesters have generally directed their own computers to support the protest.

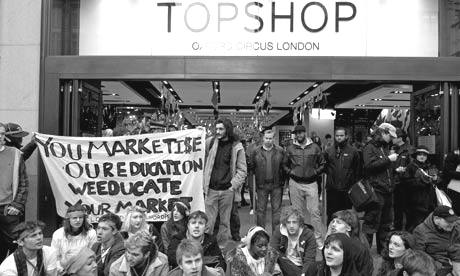

The proper comparison is with the crowds that descended last week (December 2010) on Topshop stores. They didn’t break into the stores or take any goods from them, but they sure caused a nuisance for the owner, who also “advises” the UK government — presumably to let him continue extracting money without paying tax.

I wouldn’t like it one bit if my store (supposing I had one) were the target of a large protest. Amazon and MasterCard don’t like it either, and their clients were annoyed. Those who hoped to buy at Topshop on the day of the protest may have been annoyed too.

The Internet cannot function if web sites are frequently blocked by crowds, just as a city cannot function if its streets are constantly full of protests. But before you support a crackdown on Internet protests, consider what they are protesting: in the Internet, users have no rights. As the Wikileaks case has demonstrated, what we do in the Internet, we do on sufferance.

In the physical world, we have the right to print and sell books. Anyone trying to stop us would need to go to court. That right is weak in the UK (consider superinjunctions), but at least it exists. However, to set up a web site we need the cooperation of a domain name company, an ISP, and often a hosting company, any of which can be pressured to cut us off.

In the US, no law explicitly requires this precarity. Rather, it is embodied in contracts that we have allowed those companies to establish as normal. It is as if we all lived in rented rooms and landlords could evict anyone at a moment’s notice.

Reading too is done on sufferance. In the physical world, you can buy a book anonymously with cash. Once you own it, you are free to give, lend, or sell it to someone else. You are also free to keep it. However, in the virtual world, “e-book readers” have digital handcuffs to stop you from giving, lending or selling a book, as well as licenses to forbid that. In 2009, Amazon used a back door in its e-book reader to remotely delete thousands of copies of 1984, by George Orwell. The Ministry of Truth has been privatized.

In the physical world, we have the right to pay money and to receive money — even anonymously. On the Internet, we can receive money only with the approval of organizations such as PayPal and MasterCard, and the security state tracks payments moment by moment. Punishment-on-accusation laws such as the Digital Economy Act extend this pattern of precarity to Internet connectivity.

What you do in your own computer is also controlled by others, with nonfree software. Microsoft and Apple systems implement digital handcuffs — features specifically designed to restrict users. Continued use of a program or feature is precarious too: Apple put a back door in the iPhone to remotely delete installed applications. A back door observed in Windows enables Microsoft to install software changes without asking permission.

I started the free software movement to replace user-controlling nonfree software with freedom-respecting free software. With free software, we can at least control what software does in our own computers. The LOIC program used for Anonymous protests is free software; in particular, users can read its source code and change it, so it cannot impose malicious features as Windows and MacOS can.

The US state today is a nexus of power for corporate interests. Since it must pretend to serve the people, it fears the truth may leak. Hence its parallel campaigns against Wikileaks: to crush it through the precarity of the Internet and to formally limit freedom of the press.

Disconnecting WikiLeaks is comparable to besieging (“kettling”) protesters in a London square. Preemptive police attacks provoke reaction; then they use the small wrongs of an angry people to distract from the giant wrongs of the state. Thus, the UK arrested the protester who swung from a flag, but not the man (presumably a cop) who cracked a student’s skull. Likewise, states seek to imprison the Anonymous protesters rather than official torturers and murderers. The day when our governments prosecute war criminals and tell us the truth, Internet crowd control may be our most pressing remaining problem. I will rejoice if I see that day.

Copyright 2010 Richard Stallman

Released under the Creative Commons Attribution Noderivs License.

Graphic editable sources: anonymous.svgz

Topshop stores image: The Guardian